No Representation without Taxation

As illustrated by the annual Oxfam report An Economy for the 1% dating from the 18th January 2016, the richest 1% of the world population now possesses as much wealth as the rest of the world combined. This fact indicates that wealth is accumulating in fewer and fewer hands, leading to deepening severe inequalities as well as to pressing problems – such as lack of proper housing, no access to water or to sanitary facilities, no shelter from diseases. Hence, there seems to be a desperate need for a fairer distribution of resources.

A well-known instrument of partial redistribution within societies is taxation, especially the progressive system, which applies a higher tax rate on the individuals detaining more resources (i.e. the wealthiest ones). Of course, personal taxation is not the only instrument. As well as individuals, corporations too have an income. Thus, they are subjected to taxes, in this case named “Corporation income tax”. The money collected through taxation is later on supposed to be used by governments to finance the production of public goods – for instance, public health – and the provision of benefits to the ones in need.

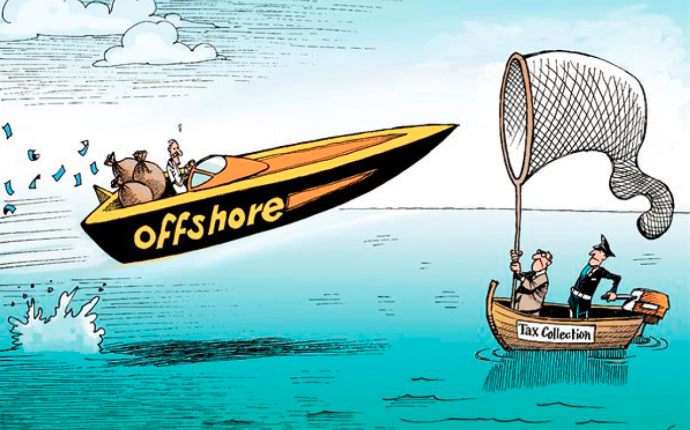

However, the efficacy of this instrument is undermined by the increasingly fiscal competition between countries. In an interconnected world, changing of headquarter or moving in another country is relatively easy for the big corporations (even more so if the siege is only de jure and not de facto) as well as for rich persons. As a result, certain countries take advantage of this and propose advantageous tax rates. A good example of this situation is the “Imposition d’après la dépense” implemented in most of the Swiss cantons (and other countries) to attract rich foreigners, or the barely inexistent Effective Corporation Income Tax Rate in countries such as Ireland (8%) and Bermuda (2%)[1]. Consequently, other States – fearing an exodus of important taxpayers, who happily use this leverage – are almost obliged to not increase their rates or even to decrease them. This results in a loss of incomes for governments, subsequently leading to fewer resources available to assist the poorest classes of the population. Therefore, it leads to a decline of redistribution and, one might say, of justice: having to decrease tax rates for corporations, the risk is that countries may increase the rates for the lower and middle classes, who don’t dispose of as much leverage as the big corporations, or that the social services provided will decline both in quantity and quality.

Since the solution cannot originate within the domestic boundaries, the consequence being the likely departure of multinationals and rich residents to another tax haven, the issue has to be tackled at the international level by harmonising the tax systems. Such a policy would certainly be extremely difficult to implement, as taxation is at the core of national sovereignty and furthermore because the countries offering lower rates would probably not want to collaborate. A third obstacle would be the heterogeneity of the national mechanisms; it would not be easy to reach an agreement between countries with high tax rates but with a strong social orientation – such as the Scandinavian States – and others more liberally driven, for instance the United States. Nevertheless, it is the only possibility to improve the current state. A possible solution to the latter complication could be to start with regional mechanisms, which would plausibly reduce the differences between different systems. In this scenario, the European Union could act as a bridgehead, since it is the most advanced regional union in the world. With regard to the first two issues, a change could arise from a sudden crisis related to the increasing inequalities, which could result in popular uprisings, state bankruptcies, political instability and so forth. These issues – in a context similar to the one described by the theorists of the “punctuated equilibrium” – might lead to the realization that the system must change and bring together the vast majority of the countries into shaping a policy making the tax harmonisation possible.

During the 18th Century, the citizens of the Thirteen Colonies – tired of having to pay taxes without having the possibility to elect a representative to the British Parliament – rose against the British Empire under the slogan “No taxation without representation”. In order to improve the situation of billions of people by increasing the allocation of resources, it’s time to stand up to the multinationals and to the incredibly wealthy persons and demand: “No representation without (proper) taxation”.

Aris Dorizzi

[1] Chavagneux Christian, Ronen Palan, and Richard Murphy. Tax havens: How globalization really works. Cornell University Press, 2010.