Colombian Delusion of Development

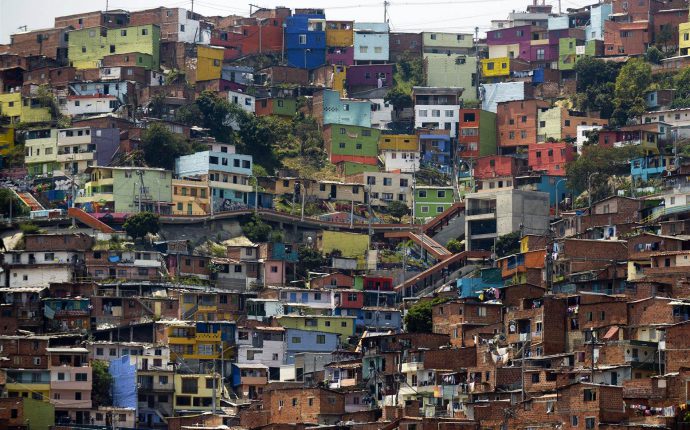

A view of Comuna 13, one of the poorest areas of Medellin, Antioquia department, Colombia, on April 1. RAUL ARBOLEDA / AFP - Getty Images

In Latin America, contemporary globalization has been associated with neoliberal economic policies that have drastically restructured governments across the continent. Since the 1990s, the Colombian government has followed a neoliberal conception of development, which has taken on peculiarities that have exacerbated violent internal conflict. In order to satisfy an export-led economic agenda, and ensure security and economic safety for investors, the Colombian government has enhanced state power within the executive branch in order to implement neo-liberal policies through a highly authoritarian regime. The result has led to increased state violence, corruption, and decreased government accountability.

The Colombian integration into a neoliberal economy simulates the same attitudes that were taking place across Latin America and the World throughout the late 1980s and the early 1990s. This process of economic globalization has been linked with neoliberal politics and structural adjustment programs imposed by international financial institutions, as well as a shift away from protectionist, mercantilist, and redistributive policies of the import substitution period of the mid-twentieth century (Chomsky 2007, 90.) At the beginning of the 1990s, together with the constitutional reforms of 1991, trade reforms in Colombia were one of the most swifts into import liberalization of Latin America, within a few months tariffs were more than halved as few private organizations were given the power to monitor trade and commerce (Bussolo and Lay 2013, p.6). Along with this these government reforms, the current global neoliberal drive to privatize, deregulate, and in general, reduce the state’s role in society in many ways mirrors the historical nature of the Colombian nature (Chomsky 2007, p.97).

These politics and policies have sought to integrate world economies by welcoming foreign investment with emphasize on exports, and the scaling back of the social-welfare state and limiting the presence of the state in general. In Colombia’s case, the state has been restricted to providing security and safety to foreign investors in remote lands of the Colombian territory. The absence, or limited presence of the state has benefited mainly the foreign mining and agriculture companies by providing them with low or uncollected taxes, non-existent environmental regulations, and subsidized credits as well as eliminating all state provisions of social services such as education, health care, and the regulation of wages (Chosmky 2007, p. 97). These characteristics of neoliberalism are paradoxical to the definitions of development and sociopolitical stability as they further divide a Colombian society victimized by a high degree of violence, corruption, and social inequality.

In 1991, with the creation of the contemporary Colombian constitution, the relationship between the nation-state and globalization was formalized. At its focal point, the new constitution aspired to gain from neoliberalism by formulating amendments within the Colombian government that guaranteed the proper environment for foreign investors to freely and securely interact in the Colombian economic market (Bussolo and Jay 2003, p.9). When the constituent assembly was convened to frame a new constitution, the government of the time was being held accountable by the population to address the escalating rates of kidnappings, bombings and assassinations that were being carried out throughout the major cities by the guerilla groups. Some scholars, therefore, argue that the aim of this new constitution was to create a more widely based and deeply rooted institutional democracy by increasing accountability of government at various levels (Williamson 1992, p.591).

The new constitution, however, further weakened the Colombian central state that has been seen as a major factor contributing to peculiarities of the country’s history, ranging from political violence to the fragmentation of social organization (Chomsky 2007, p.97). The intent to re-balance central and local governments resulted, instead, in strengthening the national executive (Williamson 1992, p. 591). This rebalance of powers transferred some major responsibilities to the cities while concentrating judicial and legislative powers within the executive branch of government. The new constitution gave nomination powers to the president to nominate and appoint judicial members, which increased presidential powers as the judiciary lost its non-partisan composition surrendering its responsibility to hold the government accountable of its actions (Revelo-Rebolledo, p.411). With the independence of the judicial system jeopardized, so too was government accountability as the ruling party could potentially control the ministry of justice, which meant in practice that high-ranking officials could face impunity in the case of irregular practices (Schedler 1999, p.16).

These domestic changes in the Colombian government occurred concurrently with George H. W. Bush’s launch of the Andean Initiative in 1991 to encourage the production of legal exports by granting Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador some tariff concessions allowing access to US markets (Higginbottom 2005, 122). This initiative was one of the first of its kind in which neoliberalism was aimed at Latin America with full force. The incoming investment to Colombia from abroad was concentrated in the extractive industry, oil and coal especially, whose products are shipped straight out for export (Higginbottom 2005, 122). With an export oriented economy where raw materials are the substantial asset of the Colombian economy, the Colombian government loosened legislative regulations to allow mining of these resources, while also flexibilizing laws to adopt aggressive anti-union policies, resulting in the fierce repression of unions and communities mobilizing against state expenditure cuts and privatization (Higginbottom 2005, p.122). President Gaviria’s apertura or ‘opening’ of the domestic economy to foreign competition in 1990 was intertwined with democratic reforms, sealed in the 1991 constitution.

The establishment of an export-led economic agenda through constitutional means also required guaranteed economic security and safety for investors. The government faced a huge obstacle in providing the adequate economic security and safety for investors. The pre-existing rivalry between left-winged guerilla movements and right winged elites, which has produced a 60-year long civil war, posed a significant threat to neoliberalism in Colombia. The underlying causes of this political violence revolve around broad factors such as unequal access to economic power, especially land and resources, and unequal access to political power, which ultimately, are institutional factors related to the creation of guerrilla and paramilitary violence World Bank 2000, p.6). The Colombian civil war is a war that also involves competition for the control of land. The increased demand to secure and retake land in order to guarantee foreign investment transformed a remote guerilla activity into country-wide war, bringing in paramilitary groups and other social actors, which have included both external and internal changes relating to economic liberalization consisting of coal and oil developments (World Bank 2000, p.5).

Pressures for economic liberalization and pressure to control economically significantly land came from the World Bank, US trade representatives, as well as Colombian exporters (Aviles 2006, p. 390). Investment from abroad initiated from US aid in combating opposition groups and guerillas with the intent of eliminating the internal conflict and bringing an end to the drug trade (Higginbottom 2005, p.123). Between 1990 and 1993 Colombia was the leading recipient in military aid in all of Latin America to support the war on drugs, but is was contingent upon the opening and restructuring of these economies along neoliberal lines (Aviles 2006, p391). Multiple failed attempts by the Colombian government to disarm and demobilize the two main guerilla groups; Revolutionary armed forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN), through peace treaties ultimately led to the use of the rightist paramilitaries to unleash an extraordinary wave of violence to crush the leftist unions.

By 1995, despite the extensive foreign military aid being received, the guerillas had the upper hand in many parts of the country. State officials acted rapidly to reorganize the already existing right wing paramilitary groups (Higginbottom 2005, p. 123). The Colombian government, in its urgency to defeat opposition and provide security, constructed policies that classified deaths arising from conflict as ‘muertes de combate’ or deaths of combat, which legitimized the use of force and executions as a method of bringing security at all costs (MRC 2014, p.25). The Colombian government funded the paramilitary groups and allowed them to take responsibility of all the illegal work the government was unable to undertake due to international law and regulation.

All the tactics used by the Colombian government had shown few results as the new constitution in 1991 along with its paramilitary alliance were insufficient to co-opt major sources of political opposition (Aviles 2006, p. 402). As the FARC doubled in numbers and pressures from Washington began escalating urging the Colombian government ‘to wage an all-out war against guerillas’ as the condition for more aid, foreign investment, and trade (MRC 2014, p. 17-18), the paramilitary groups, along with the military forces, used extra-judiciary executions as their main tactic in producing positive results in the fight against the guerillas (CINEP/PPP 2011, p.6). Extra-judicial executions were product of a criminal plan which it’s sole purpose was to satisfy an institutional demand, born from the necessity to demonstrate at the high military commanders, the Colombian government, and international institutions that the war against the illegal armed groups was being won (CINEP/PPP 2011, p. 8). These illegal acts were further intensified by an international phenomenon that affected the whole world.

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 on the US shifted political, economic, and military priorities around the world. This event caused fundamental changes in Colombia’s neoliberal policies and economic efforts by transforming the Colombian state from an armed neo-liberal state to a neo-conservative regime (Rico-Revelo 2008, p.12). The shift occurred under the administration of George W. Bush in cooperation with the administration of Colombian president Alvaro Uribe Velez as both implemented hard and strict neoliberal doctrines in their government policies. After his election in 2002, president Uribe implemented a highly authoritarian, neo-conservative regime that internalized the Bush doctrine (Higginbottom 2005, p.124). The doctrine, facilitated by a weak judicial system, allowed Uribe and his executive government to give absolute priority to internal social control and further concentrate the state’s powers and duties towards fighting the FARC and other guerilla movements (Revelo-Rebolledo 2008, p.56).

In Bush’s dire intent to eliminate terrorist groups, Plan Colombia was instituted as a plan to go onto an all-out offensive in Colombia against the FARC, which had been recently categorized as a terrorist group (MCR 2014, p.17). In a neoliberal context, terrorism and terrorist groups are categorized as a serious threat to democracy, but more crucially a threat to capitalism and neoliberal principles. The FARC’s extensive territorial control in Colombia presented a significant challenge to guaranteeing continued economic development and global economic integration as this territorial control was essential for providing foreign companies with more resources and territory to extract, exploit, and export. With Bush and Uribe at the forefront of this movement, Plan Colombia, would take into effect as the war effort engaged more aircraft, more soldiers, more spending by both governments, and more resources dedicated at driving the guerillas out of economically significant areas (Higginbottom 2005, p.123). This substantially increased the levels of violence in Colombia with every corner of the country becoming militarized; every aspect of Colombian society became focused on a security-state and the presence of security at all costs (Rico- Revelo 2008, p.16).

With Uribe as the president and the state’s powers concentrated on an economic model of a neo-conservative regime, the direction was to “consolidate land seizures and use them as a platform for growth” (Higginbottom 2005, p.123). In order to make this happen, the government, once again, allied with the right-wing paramilitaries. This time, however, as accusations rose against the paramilitary’s involvement in extrajudicial executions, the judiciary government preferred offering paramilitary members impunity in exchange for their demobilization. This led the government to restructure its war strategy and to rely heavily on its military forces to defeat the guerilla groups, but with the absence of the paramilitary militias to cover the government’s dirty war, scandals arose of even more extra judiciary executions being performed by the military in order to meet the expectations of Plan Colombia and to please international pressures with positive combat results (MRC 2014, p. 93-95).

The Colombian government offered monetary rewards, promotions, and compensations to military soldiers and generals for demonstrating high number of guerilla killings and captures as incentives to provide higher positive results. These incentives caused the scandal known as ‘Falsos Positivos’ or false positives. This scandal came after a multiple cases where the military recruited innocent rural civilians from distant territories and then murdered them close to guerrilla controlled territory and processed them as positive results and deaths of combat (CINEP/PPP 2011, p.6). This phenomenon was a common practice used for almost three years starting with the demobilization of the paramilitaries in 2006 and until 2008 when the scandals were publicized by the families of the victims.

Neo-liberal foreign pressure to fight terrorism and drive guerilla forces out of strategic and economic important land led Uribe to implement a highly neo-conservative authoritarian regime in his attempt in providing democratic security at any costs (CINEP/PPP 2011, p.8). A country where its military forces, strengthened by important foreign aid, systematically drawing on committing violent crimes against civil society, can’t be classified as a democracy and this systematic failure, brought upon by neo-liberal approaches, exacerbates the harmful effects neo-liberalism has had on Colombia. The United States, while condemning these acts, would repeatedly support them by continuously providing monetary and military aid (Rico-Revelo 2008, pg. 12). Low-intensity democracy was initiated and maintained by elites that allowed or promoted state and para-state repression as a necessary complement to economic and political change (Aviles 2006, p.392).

Transnational corporations associated with extractive investments, such as the oil industry played an active role in these developments. Many multinational corporations lobbied various international governments for the continuous assistance in the dispossession of economically important land. For example, the vice president of Occidental Petroleum personally lobbied for US assistance to Plan Colombia, emphasizing Colombia’s extensive oil potential and unexplored regions (Aviles 2006, p. 402). Many of those areas laid in regions under guerilla control, which required establishment of government control before exploration contracts with multinational corporations could be signed. As a matter of fact, multinationals tend to appear in places that have previously suffered from paramilitary attacks where the population has been disappeared, assassinated or displaced (Vincente et al 2011, p.6). Reports from the Consultancy on Human Rights and Displacement (CODHES) have found there to be a large military and paramilitary presence in mining zones: “The armed forces protect private investment and paramiliatries suppress social protest and create displacement (CODHES 2011).”

Military along with paramilitary repression did, or has, allegedly helped to establish security and labour peace for certain transnational corporations through their selective assasinations of union leaders, or by reinforcing protection from guerilla attacks for specific areas (Aviles 2006, p. 404). Alvaro Uribe’s term as president from 2002-2010 continued to support and promote these corrupt actions, while maintaining a neoliberal agenda that had already contributed to exacerbating social and economic inequality and conflict in Colombia. The US ‘war on terrorism’ also allowed Colombia to pursue overt authoritarian methods in the establishment of state authority and under Uribe this agenda was aggressively advanced creating a state that characterizes a neo-conservative authoritarian regime (Aviles 2006, p.406).

Poverty, inequality, and rapid growth, together with high levels of impunity within the justice system relate to the most important causes of economic and social violence in Colombia World Bank 2000, p. 17). Due to what happened in Colombia we can see how in order to satisfy an export-led economic agenda, and ensure security and economic safety for investors, neoliberalism can lead to significant dislocation within developing countries. Neoliberalism in Colombia jeopardized the division of power while stripping the executive, legislative, and judiciary of their duty in constraining each other through the classic “ check and balances” which is essential in democratic theory (Schedler 1999, 23). As a result, scholars should envision new theories of development, which take into account increased state violence, corruption, and decreased government accountability to ensure that equitable and sustainable development is possible. If not taken seriously, like the Colombian case study dictates, there may be drastic consequences. Institutional weakness, organized crime, and the exacerbation of social conflict are the only results that neoliberalism has left in Colombia, which suggests that the neoliberal locomotive might not have room for all Colombians.

David Romero (UVIC – University of Victoria, Canada)

Pour aller plus loin dans cette même thématique c’est par ici

Sources

– Bussolo, Maurzio and Lay, Junn. Globalization and Poverty Changes in Colombia November 2003, pp. 5-12.

– Centro de Investigacion y Educacion Popular/ Programa Por la Paz (CINEP/PPP). Colombia, Deuda Con la Humanidad 2: 23 años de Falsos Positivos 1988-2011, pp. 6-141.

– Chomsky, Avira![]() . Globalization, Labor, and Violence in Colombia’s Banana Zone February 2015, pp. 1-23.

. Globalization, Labor, and Violence in Colombia’s Banana Zone February 2015, pp. 1-23.

– Hissinbottom, Andy. Globalization, Violence, and the Return of the enclave to Colombia 2005, pp. 121-125

– Movimiento de Reconciliacion Coordinacio: Colombia-Europa-Estados Unidos (MRC). “Falsos Positivos” En Colombia y el papel de asistencia military de Estados Unidos: 2000-2010 June 2014, pp. 12-124

– Revelo-Rebolledo, Javier Eduardo. Experts and Fans. The Presidential nomination Power, Bureaucracy, and the Colombian State Capacity 2002-2010; July 2010, pp. 1-48

– Revelo-Rebolledo, Javier Eduardo. Judicial Independence during Uribe era February 2008, pp. 1-62

– Rico Revelo, Diana. Configuracion del Estado-Nacion En Colombia En el Contexto de Globalizacion: Una Reflexion desde el Escenario Politico April![]() 2008, pp. 3-22

2008, pp. 3-22

– Schedler, Andreas. 1999. “Conceptualizing Accountability” in The Self-Restraining State: Power and accountability in New Democracies, edited by Andreas Schedler, Larry Diamond and Marc F. Plattner, pp. 13-28

– The World Bank![]() . Violence in Colombia 2000, pp. 4-19

. Violence in Colombia 2000, pp. 4-19

– Vincente Ana, Martin Neil, James Daniel, Lefebvre Sylvain, and Bauer Briana. Colompbia: Mining in Colombia, At What Cost? November 2011, pp. 3-18

– William Aviles. Paramilitarism and Colombia’s Low-Intensity Democracy: Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 38, No. 2 (May 2006), pp. 379-408

– Williamson Edwin. 1992. “Part Four: Towards A New Era” in The Penguin History of Latin America, pp. 567-627